A reflection on Small Things Like These and the violence of looking away

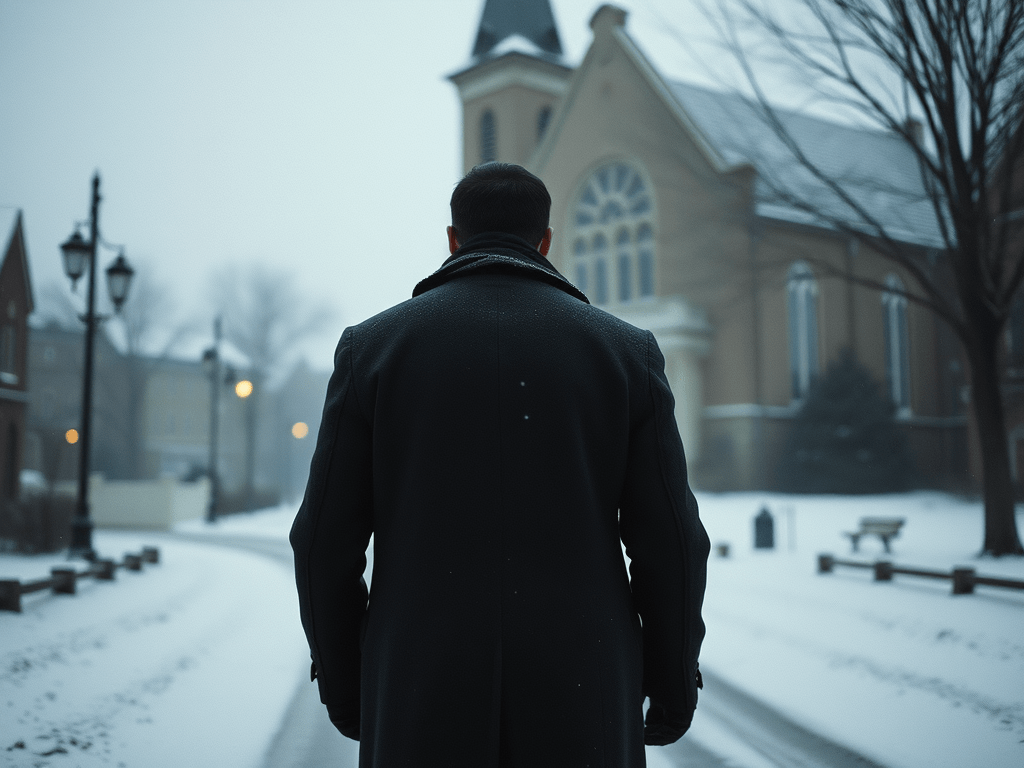

Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is a quiet book. Short, restrained, almost deliberately modest. A man going about his work. A town moving through winter. A truth that has existed in plain sight for years. There are no speeches, no dramatic reckonings, no guarantee that doing the right thing will end well.

That quiet is not accidental. It’s the point.

Keegan is interested in what happens when harm becomes ordinary—when cruelty settles into the background of daily life and stops interrupting it. This is not a story driven by revelation. Everyone already knows. The question is what people do with that knowledge, and how long they can live beside it without letting it change them.

Bill Furlong is not powerful. He’s a coal merchant trying to keep his business afloat, his daughters fed, his life steady. He belongs just enough to understand how things work. And the rules are clear: don’t ask questions, don’t cause trouble, don’t risk what you have for people no one is protecting anyway.

The Magdalene laundry isn’t hidden. The girls are right there. The Church is right there. The suffering has been absorbed into the landscape, treated like bad weather—regrettable, uncomfortable, but somehow unavoidable. Silence, in this world, isn’t ignorance. It’s how the town keeps functioning.

Keegan doesn’t pretend that speaking up is simple. Bill understands exactly what it would cost him. The risk isn’t abstract or symbolic; it’s financial, social, real. This isn’t a story about someone who doesn’t grasp the stakes. It’s about someone who does—and can’t quite settle back into himself afterward.

What unsettles him isn’t outrage so much as proximity. The girl he encounters isn’t there to symbolize anything larger. She’s cold. Tired. Reduced by a system that has learned how to make people manageable. What breaks through Bill’s restraint is memory—his own fragile beginnings, the awareness that his life could have gone another way if one woman hadn’t intervened years earlier. Decency, here, isn’t theoretical. It’s personal, which makes it harder to ignore.

This is where the novel sharpens. It exposes the comforting lie that silence is neutral. Silence doesn’t stop harm; it steadies it. It allows violence to continue without ever needing to call itself violent.

That dynamic isn’t confined to the book’s setting or its time. It’s uncomfortably familiar. You see it in the way immigrants are assaulted, detained, and held in inhumane conditions while debates center on legality instead of humanity. You see it in the way women watch their abusers remain free—protected, rebranded, even respected—while they’re told, implicitly or explicitly, that speaking didn’t change anything. The truth is known. The harm is documented. And still, the burden settles with the people who were hurt, while powerful men continue on, largely untouched. Silence, in these cases, isn’t accidental. It’s the mechanism that allows reputation and power to outlast accountability.

Keegan also understands something more complicated: silence is often learned. For many women, especially, speaking up isn’t an abstract moral choice. It’s shaped by experience—by remembering what happened the last time the truth was told. Disbelief. Retaliation. Isolation. Sometimes nothing at all. In those situations, silence can feel less like indifference and more like survival.

The novel doesn’t dismiss that reality. But it also doesn’t let understanding turn into absolution. Knowing why people stay quiet doesn’t erase what that quiet allows to continue. Keegan holds that tension without resolving it, which is what makes the book linger. There’s no version of this story that lets the reader feel both informed and untouched.

Bill’s choice doesn’t dismantle the Church or redeem the town. It doesn’t promise safety or closure. That’s exactly why it matters. Keegan pushes back against the idea that moral action only counts if it produces visible change. The question she keeps returning to is simpler and more unsettling: not whether the system will fall, but whether you will keep helping it stand.

Reading Small Things Like These now, at a moment when silence is often reframed as civility, neutrality, or self-preservation, it feels less like a historical novel and more like a mirror. We’re encouraged constantly to stay out of it, to look away, to focus inward. Institutions depend on that instinct. It keeps everything running smoothly.

Keegan doesn’t offer comfort in return. She doesn’t let responsibility be outsourced to history, authority, or exhaustion. She insists on something quieter and harder to sit with: proximity creates obligation. Once you see something clearly, you’re changed by it. Silence, even when understandable, is still a choice.

The title isn’t ironic. The small things are the point. The moments we tell ourselves it’s not our place, not our fight, not the right time. The choices we make to stay comfortable instead of attentive.

This book doesn’t ask us to be heroes. It asks us to notice what we already see—and to sit honestly with what it costs to look away.

Leave a comment